there exists an ε, such that for any N, we can find n>N satisfying |a n-L| ≥ ε. įor our problem, suppose ( a n) → L.The sequence a n does not converge to L if and only if: “It is not true that there exists x, P( x) holds.” → “For any x, P( x) doesn’t hold.”Īpplying this rule-of-thumb recursively, we see that:.“It is not true that for every x, P( x) holds.” → “There exists x, P( x) doesn’t hold.”.what does it mean to say that a n does not converge to L? There’s a nice trick to take the negation of such statements: We need to take the negation of the definition, i.e. Prove that the sequence a n= (-1) n is not convergent. Which shows that the sequence converges to 3. ♦Įxample 3.

For each ε>0, we need to establish an N such that when n > N, we have | a n – 0| 0, we set N = 6/ε. Prove that if a n= 1/ n, then ( a n) → 0. for every positive real ε, there exists N, such that whenever n>N, we have |a n – L| N, we have | a n– K| M, we have | a n– L| max( M, N) such thatĮxample 1.

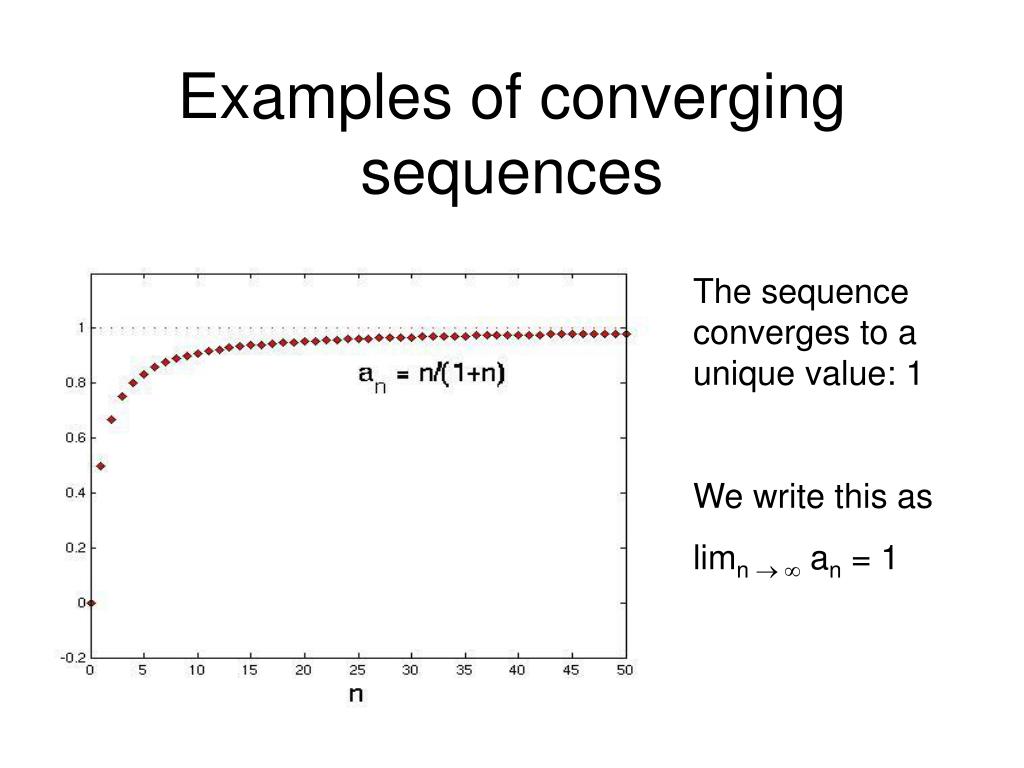

We say that (a n) converges to a real number L (written a n → L) if: One can think of it as a function N → R, where N is the set of positive integers. Our focus here is to provide a rigourous foundation for the statement “sequence ( a n) → L as n → ∞”.ĭefinition (Convergence). Definition of ConvergenceĪ sequence in R is given by ( a 1, a 2, a 3, …), where each a i is in R. Thus, L = sup(S) iff (i) L is an upper bound, (ii) for each ε>0, there exists x in S, x > L-ε. Since L-ε is not an upper bound, there exists x in S, x > L-ε. the set of real (or rational) numbers 0 0).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)